How Career Mobility can drive greater diversity and inclusion - and is key to increasing retention

Contributors:

Jackie Ford, Professor, Durham University

Judy Ellis, SVP of DEI Advisory, AMS

Paul Modley, DEI Managing Director, AMS

During 2021, more than 47 million Americans voluntarily quit their jobs according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Worker shortages are everywhere, with analysts from Goldman Sachs recently claiming the US is in the midst of its biggest talent shortage for 80 years - and that more jobs are available than workers can fill.

With organisations competing to fill positions and candidates fielding multiple offers, companies are being forced to massively hike salaries to ensure existing talent stays, while at the same time struggling to bring new hires onboard.

Issues like candidate ghosting - where hires cut contact with an employer or even fail to turn up on their first day, having found a better offer - are growing, with 28% of jobseekers admitting to ghosting and 8% simply not turning up, according to a 2021 Indeed survey.

Mobility as a tool for retention and driving diversity

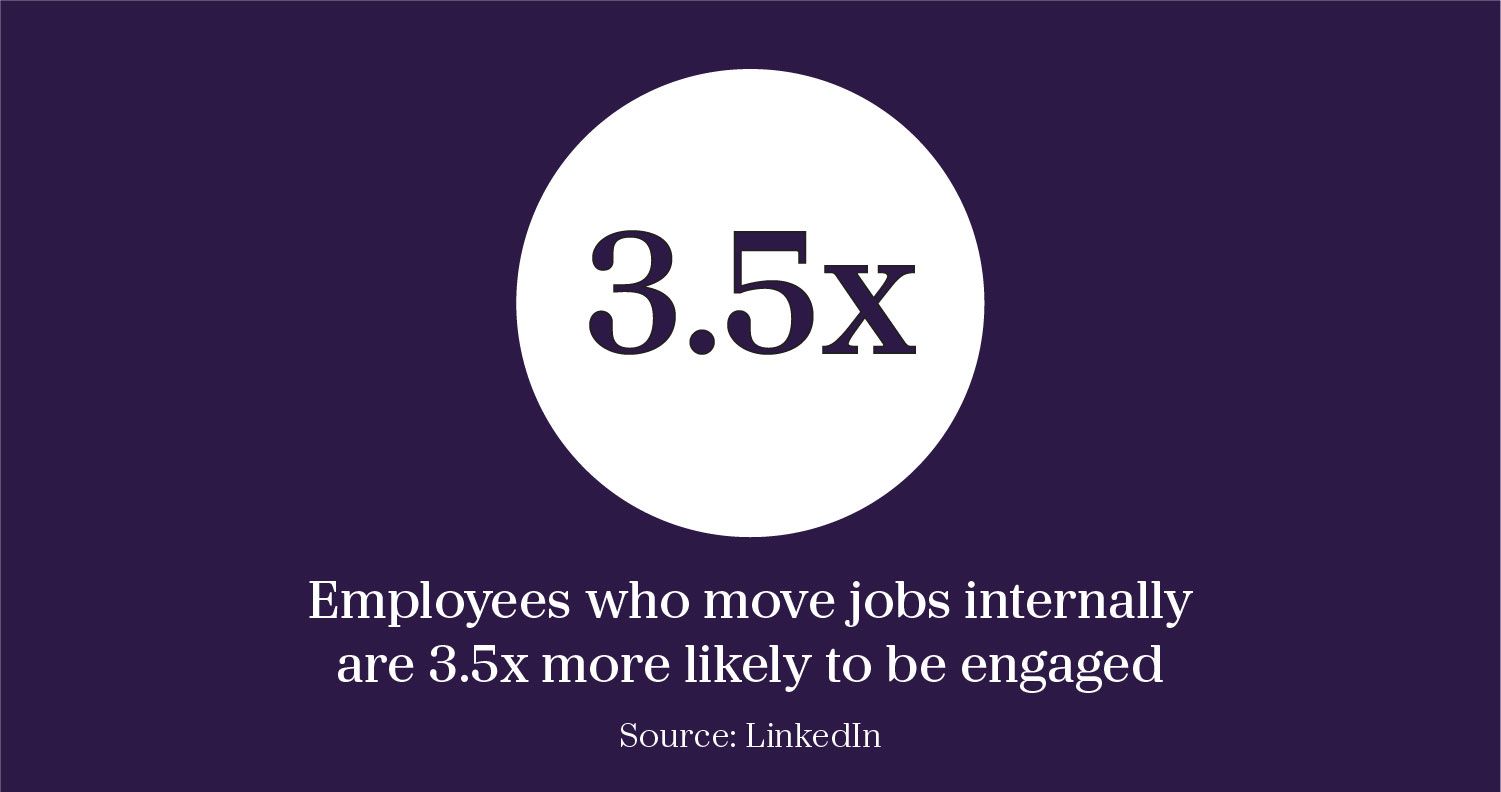

One defence against the competing need for new talent and retaining existing employees is career mobility. Not only does it provide employees with opportunities for growth, development and reskilling, but it also can help drive another key metric for many businesses - greater diversity and inclusion.

In fact, mobility and diversity and inclusion leaders face similar challenges. Both are looking to attract the best talent and develop future skills capabilities, both are looking to fill talent gaps, and both are looking for new ways to engage and retain their best people. So how can talent leaders improve diversity and inclusion through career mobility?

“Research by JR Keller and others has shown that internal hires outperform external hires. Organisations have much more information about internal candidates than external ones, so businesses are increasingly thinking of their existing employees as ‘talent rich’ and looking at how they can utilise their skills in different roles,” says Judy Ellis, senior vice president of DEI, advisory at AMS.

“The problem is that internal moves and promotions tend to be a result of the network of the person looking to move. When you’re dealing with diversity, typically the more your dimensions of diversity separate you from the mainstream, the less networked you are and the less people are aware of your accomplishments,” she adds.

Combating this ‘who you know, not what you know’ culture requires being more explicit about the opportunities available internally and better understanding the capabilities of your existing talent.

This could mean creating a talent marketplace by posting all roles internally and looking at sponsorship of underrepresented high potential talent, placing them in specific talent programmes where they have access to senior leaders and their skills and accomplishments are exposed to new networks and opportunities.

It also means being aware of how your internal communications and employee engagement strategies impact different demographics. Two-way communication is key.

“I’ve seen issues with getting women and people of colour to apply for internal roles. In focus groups I conducted for clients, many saw internal postings as perfunctory, believing hiring managers had already chosen their desired candidate, so few believed in the process. At the same time, senior leaders were wondering why they had a lack of underrepresented applicants,” says Ellis.

“I found unsuccessful candidates often received no feedback about why they weren’t selected for a role. Therefore, when they saw the position filled by someone else, they determined the hiring manager had ‘pre-selected’ them. Failing to close the communication loop with unsuccessful candidates impacts them and everyone they talk to. Hiring managers should give specific feedback to candidates so they understand how to build their capabilities. While this may seem labour intense, it pays dividends to the individual and their network, instilling confidence in the overall process,” she adds.

During 2021, more than 47 million Americans voluntarily quit their jobs according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Worker shortages are everywhere, with analysts from Goldman Sachs recently claiming the US is in the midst of its biggest talent shortage for 80 years - and that more jobs are available than workers can fill.

With organisations competing to fill positions and candidates fielding multiple offers, companies are being forced to massively hike salaries to ensure existing talent stays, while at the same time struggling to bring new hires onboard.

Issues like candidate ghosting - where hires cut contact with an employer or even fail to turn up on their first day, having found a better offer - are growing, with 28% of jobseekers admitting to ghosting and 8% simply not turning up, according to a 2021 Indeed survey.

Mobility as a tool for retention and driving diversity

One defence against the competing need for new talent and retaining existing employees is career mobility. Not only does it provide employees with opportunities for growth, development and reskilling, but it also can help drive another key metric for many businesses - greater diversity and inclusion.

In fact, mobility and diversity and inclusion leaders face similar challenges. Both are looking to attract the best talent and develop future skills capabilities, both are looking to fill talent gaps, and both are looking for new ways to engage and retain their best people. So how can talent leaders improve diversity and inclusion through career mobility?

“Research by JR Keller and others has shown that internal hires outperform external hires. Organisations have much more information about internal candidates than external ones, so businesses are increasingly thinking of their existing employees as ‘talent rich’ and looking at how they can utilise their skills in different roles,” says Judy Ellis, senior vice president of DEI, advisory at AMS.

“The problem is that internal moves and promotions tend to be a result of the network of the person looking to move. When you’re dealing with diversity, typically the more your dimensions of diversity separate you from the mainstream, the less networked you are and the less people are aware of your accomplishments,” she adds.

Combating this ‘who you know, not what you know’ culture requires being more explicit about the opportunities available internally and better understanding the capabilities of your existing talent.

This could mean creating a talent marketplace by posting all roles internally and looking at sponsorship of underrepresented high potential talent, placing them in specific talent programmes where they have access to senior leaders and their skills and accomplishments are exposed to new networks and opportunities.

It also means being aware of how your internal communications and employee engagement strategies impact different demographics. Two-way communication is key.

“I’ve seen issues with getting women and people of colour to apply for internal roles. In focus groups I conducted for clients, many saw internal postings as perfunctory, believing hiring managers had already chosen their desired candidate, so few believed in the process. At the same time, senior leaders were wondering why they had a lack of underrepresented applicants,” says Ellis.

“I found unsuccessful candidates often received no feedback about why they weren’t selected for a role. Therefore, when they saw the position filled by someone else, they determined the hiring manager had ‘pre-selected’ them. Failing to close the communication loop with unsuccessful candidates impacts them and everyone they talk to. Hiring managers should give specific feedback to candidates so they understand how to build their capabilities. While this may seem labour intense, it pays dividends to the individual and their network, instilling confidence in the overall process,” she adds.

The problem is that internal moves and promotions tend to be a result of the network of the person looking to move.

Demographics are not homogenous

Professor Jackie Ford is professor of leadership and organisation studies director at Durham University Business School. With colleagues, she has just completed a three year research project into diversity and inclusion challenges in the UK retail sector, focusing on 70,000+ employer Marks and Spencer.

She believes that one of the biggest mistakes organisations make when implementing diversity and inclusion initiatives is to treat all groups as one homogenised demographic with the same needs and desires.

“Leaders sometimes make assumptions about people who present with particular characteristics, whether those with disabilities, older women or different ethnicities. They make assumptions about how to support them or what they might want, rather than just asking them,” says Ford.

This can disengage employees and lead to inconsistency between what diversity initiatives are trying to achieve and what they actually do.

Ford gives two examples from the study. The first involves older female workers, who were seen as both valuable sources of knowledge and experience, but also as coming to the end of their careers and unlikely to want to get involved. The second is around talent hired from competitors to modernise the brand, but who were blocked by senior leaders who were unreceptive to their ideas - despite hiring them for this very reason. Poor communication and a lack of transparencies around your procedures can very quickly hinder culture change.

“Don’t just look at people as one culture or demographic and don’t assume one size fits all. If you make assumptions about how people will behave, the danger is that is what they will become and you won’t change,” says Ford.

The role of leaders

Having a disconnect between employee value propositions and what you actually deliver can lose you diverse talent - so it is vital leaders set the right example.

“Organisations are working really hard to hire the talent they need, so it’s incumbent on all leaders to create an environment that supports diverse talent and matches what they were sold in the hiring process,” says Paul Modley, director diversity, equity and inclusion at AMS.

Doing so means hiring diverse talent with a view to progressing them through the organisation, not just getting them in the door. The opportunity to develop is the key to retaining all talent.

“When it comes to making your organisation more diverse, yes you’re hiring for a particular role, but you also need to be thinking about roles down the line,” says Modley.

For Modley, there are two reasons for this. Firstly, diverse talent needs to see progression pathways and role models in senior positions so that they know an organisation is serious about representation at the top level. Secondly, in a candidate driven market, progression means retention.

“All organisations are looking to hire diverse talent, so if they can see brilliant career mobility programmes, they’re more likely to stay with you. More importantly, if you’re selling the dream to candidates about the diversity of your organisation but they come in, look upwards and can’t see anybody like themselves, then the organisation has failed,” he says.

Some businesses are taking a very proactive approach to career mobility, with Modley detailing one organisation that set up an internal headhunting desk, where career mobility consultants were expected to understand the skills base of existing employees and actively encourage them to apply for internal roles.

While this might not be a cultural fit for most organisations, it does exemplify current market trends. In a talent scarce world, progressing the right candidates from within can improve employee engagement, motivation and reduce time to hire. Providing the right pathways for diverse talent gives businesses - and employees - the chance to finally make our management teams more representative. It’s the right thing to do.

Written by the Catalyst Editorial Board

with contributions from:

Jackie Ford

Professor, Durham University

Judy Ellis

SVP DEI Advisory, AMS

Paul Modley

DEI Managing Director, AMS

Demographics are not homogenous

Professor Jackie Ford is professor of leadership and organisation studies director at Durham University Business School. With colleagues, she has just completed a three year research project into diversity and inclusion challenges in the UK retail sector, focusing on 70,000+ employer Marks and Spencer.

She believes that one of the biggest mistakes organisations make when implementing diversity and inclusion initiatives is to treat all groups as one homogenised demographic with the same needs and desires.

“Leaders sometimes make assumptions about people who present with particular characteristics, whether those with disabilities, older women or different ethnicities. They make assumptions about how to support them or what they might want, rather than just asking them,” says Ford.

This can disengage employees and lead to inconsistency between what diversity initiatives are trying to achieve and what they actually do.

Ford gives two examples from the study. The first involves older female workers, who were seen as both valuable sources of knowledge and experience, but also as coming to the end of their careers and unlikely to want to get involved. The second is around talent hired from competitors to modernise the brand, but who were blocked by senior leaders who were unreceptive to their ideas - despite hiring them for this very reason. Poor communication and a lack of transparencies around your procedures can very quickly hinder culture change.

“Don’t just look at people as one culture or demographic and don’t assume one size fits all. If you make assumptions about how people will behave, the danger is that is what they will become and you won’t change,” says Ford.

The role of leaders

Having a disconnect between employee value propositions and what you actually deliver can lose you diverse talent - so it is vital leaders set the right example.

“Organisations are working really hard to hire the talent they need, so it’s incumbent on all leaders to create an environment that supports diverse talent and matches what they were sold in the hiring process,” says Paul Modley, director diversity, equity and inclusion at AMS.

Doing so means hiring diverse talent with a view to progressing them through the organisation, not just getting them in the door. The opportunity to develop is the key to retaining all talent.

“When it comes to making your organisation more diverse, yes you’re hiring for a particular role, but you also need to be thinking about roles down the line,” says Modley.

For Modley, there are two reasons for this. Firstly, diverse talent needs to see progression pathways and role models in senior positions so that they know an organisation is serious about representation at the top level. Secondly, in a candidate driven market, progression means retention.

“All organisations are looking to hire diverse talent, so if they can see brilliant career mobility programmes, they’re more likely to stay with you. More importantly, if you’re selling the dream to candidates about the diversity of your organisation but they come in, look upwards and can’t see anybody like themselves, then the organisation has failed,” he says.

Some businesses are taking a very proactive approach to career mobility, with Modley detailing one organisation that set up an internal headhunting desk, where career mobility consultants were expected to understand the skills base of existing employees and actively encourage them to apply for internal roles.

While this might not be a cultural fit for most organisations, it does exemplify current market trends. In a talent scarce world, progressing the right candidates from within can improve employee engagement, motivation and reduce time to hire. Providing the right pathways for diverse talent gives businesses - and employees - the chance to finally make our management teams more representative. It’s the right thing to do.

Written by the Catalyst Editorial Board

with contributions from:

Jackie Ford

Professor, Durham University

Judy Ellis

SVP DEI Advisory, AMS

Paul Modley

DEI Managing Director, AMS